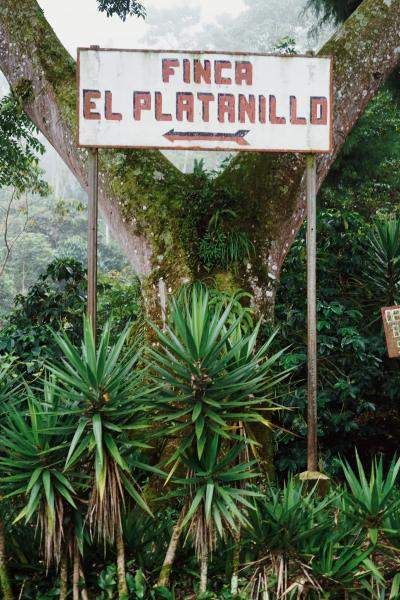

When photographer Creagh Cross visited Finca El Platanillo, a 347-hectare Rainforest Alliance Certified coffee farm in western Guatemala, he was astounded by how wild and lush the land was. “It’s amazing the pickers can even find the coffee cherries,” because the vegetation is so thick, Cross said. But as he spent more time there, photographing the harvest, Cross was even more struck by the owners’ commitment to the well-being of Platanillo’s workers.

The Coto family, who bought this land in the 1970s, was determined from the start to keep the mountainside as pristine as possible. When Stuardo Coto took over from his father in 1985, he deepened that commitment—not only to the land, but to the people who worked it, in part because he understood that a workforce treated with dignity would be more invested in protecting the mountain. That’s why the Cotos pay their workers more than the government requires and provide comfortable housing. They also built a school for students of pre-school age through high school that serves the entire area. A special program for older students focuses on growing coffee in harmony with nature—the Platanillo way.

Sign up for useful tips to green your life and protect our planet.

The Cotos’ commitment to nature and community well-being also happens to be the Rainforest Alliance way. In fact, when Stuardo and his son Samuel (who now helps run operations) decided to pursue certification in the 2000s, they discovered that they were already meeting many of our rigorous sustainability requirements. They not only achieved Rainforest Alliance certification, but in 2011 Finca El Platanillo became the first coffee farm in the world to achieve “climate-friendly” verification through our then-new climate module. Climate-smart practices have since been built into the Rainforest Alliance standard, but the Cotos’ early adoption of these methods just show how forward-thinking they are—they are truly sustainability visionaries.

Below we share with you some of Cross’s spectacular photos of harvest time at Finca El Platanillo.

If it weren’t for the sign, Cross says, you’d think you were entering a forest, not a farm.

Two pickers collect fallen cherries off the ground. While most coffee varieties turn red when ripe, this varietal produces yellowish cherries.

On average Juan, a year-round worker, picks 100-200 pounds of cherries a day, which produce 20-40 pounds of coffee beans.

Project manager Jorge Manasilla, who has worked on the farm his entire adult life, helps oversee quality control.

A coffee picker wearing a corte, a traditional Maya skirt.

A picker hauls a bag of ripe coffee cherries to the farm’s wet mill to be weighed, recorded, and sorted by bean quality. Workers may also leave their bags by the side of the road to be picked up by a truck later in the day.

In the late afternoon, after the rain, bags of newly picked cherries are weighed, so workers may be paid accordingly. The cherries are poured into a trough, then move through a maze of water channels for cleaning; they are then separated by density, which determines the quality of the coffee. Here a worker at the Finca El Platanillo wet mill scoops beans ready for drying. Another worker will lay out the beans in a thin layer across a concrete slab to continue the drying process.

These two women work in the wet mill, primarily with the specialty small batch coffees, in a phase of the process that can largely be done from a sitting position—a good thing since the woman on the left is pregnant. Moments before this was taken the woman on the right had been rubbing her friend’s belly and talking baby-talk to it, which is why they are cracking up here.

About 20 years ago, Finca El Platanillo partnered with one of its long-time customers to create the Nuevo Platanillo School, which serves children in the larger community—not just farm kids—from pre-school through high school. Built on land donated by the Cotos, the school recently added a computer lab with Internet access, and even the youngest children learn computer skills. High school students can study sustainable coffee production. It’s important to the Cotos not only to take care of the people who live and work on their farms, but to promote the ideals of the farm—growing coffee in harmony with nature—to people throughout their area.

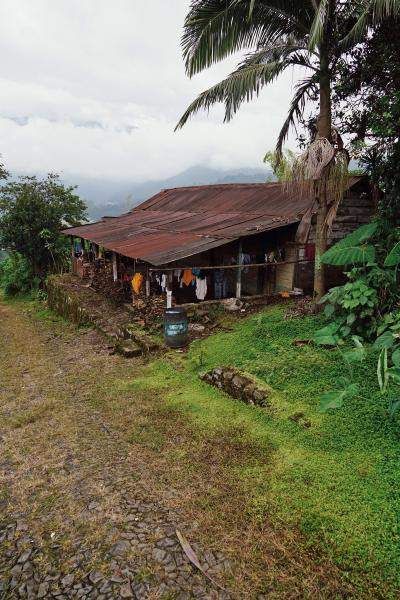

“Everything blends perfectly with the forest—every structure looks like a treehouse,” Cross says. This is one of the worker’s home. Recycling and composting are the norm, and the farms’ main kitchens serve locally sourced food. The cinderblock houses and their sheet metal roofs are built to withstand the daily heavy rains.

“All the colors you see after the rain are absolutely stunning—it’s not just green, it’s orange and red and purple and blue,” Cross says. “Because of the fog it looks different every ten minutes.”

Worker housing opens onto a communal patio that also serves as a basketball court and soccer field. Here some teenagers play a quick game of soccer in the aftermath of an afternoon downpour. Cross says that while the harvest makes for an intense schedule—pickers are in the field by sun-up, so they can finish at noon when the rains begin—they are home in the afternoon and evening to enjoy their families.

This is an experimental lot where varietals are planted in small batches to test for character traits like cherry size, and for resilience to pests and diseases, such as the roya fungus. When a varietal meets the farm’s high standards for production and quality it gets assigned a lot of its own for mass production.

Samuel (left) and his father Stuardo Coto believe that a happy workforce is more likely to safeguard the land. It’s also important to Stuardo, whose father was born on a coffee farm, to remember his roots and treat everyone around him with dignity and respect.

The sun rises over Finca El Platanillo, which is nestled in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas Mountains.