There’s no doubt about it: These are troubling times. Climate change had already cast its terrible shadow over our lives when COVID-19 brought the world to near-halt—and experts say we can expect more pandemics down the line. But it just so happens that the way to tackle the twin threats of pandemics and climate change is the same: forest conservation.

According to the UN International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), natural climate solutions (such as thriving tropical rainforests) can help us achieve 37 percent of the emissions reductions needed to stave off a climate catastrophe. Conserving forests is also key to preventing pandemics, since it’s forest destruction that brings wildlife—which are reservoirs for pathogens like the novel coronavirus—into closer proximity with each other and humans. As the UN environment chief, Inger Andersen, said early in the COVID-19 outbreak: “Nature is sending us a message with the coronavirus pandemic. Failing to take care of the planet means not taking care of ourselves.”

The Rainforest Alliance has long been on the vanguard of forest conservation. Though we tailor our solutions to local conditions, the heart of our approach remains the same across geographies: We always work to improve local livelihoods, since those who make their living from the land have the most incentive to protect it. Here are just a few forest-conservation measures that we employ, all of which help to prevent pandemics and slow climate change.

Community forestry

Community forestry—i.e. people living from their forest resources—has existed since time immemorial. But in the modern era, when the tradition of living in harmony with nature faces such grave threats, the Rainforest Alliance brings a crucial element to community forestry: responsible enterprise.

In Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve, the forest communities we work with harvest timber sustainably (e.g. one tree per hectare every 40 years), and collect tree nuts and xate (a palm frond used in floral arrangements) from the forest floor as a way of making a living from the forest while protecting it. For more than 20 years, these communities have maintained an impressive near-zero deforestation rate in a region otherwise devastated by deforestation—and they’ve done so while building bustling local economies.

Digital innovations to stop forest destruction

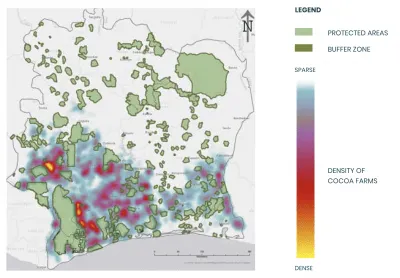

Technology offers a way to reach farmers and forest communities across vast distances, and the Rainforest Alliance has made the most of this connectedness with apps that deliver individualized coaching to farmers and advice on climate-related problems like the coffee-plant fungus, roya. Needless to say, we have also tapped into the latest technology to stop deforestation. Our risk maps, for example, overlay manually created farm maps with forest data collected using remote-sensing devices. In our 2020 certification program, auditors can use custom risk maps and accurate spatial data to help determine if there are deforestation risks even before stepping foot on a farm. If risks exist, the auditor knows to pay close attention to them, thereby helping farmers avoid deforestation.

(Disclaimer: The map is based on the locations of 240,948 UTZ cocoa farms certified in Ivory Coast for 2019-2020. The data came from the certified farm groups and third-party sources and was received by 2020 April 6. The Rainforest Alliance cannot guarantee the full accuracy of the data. This map cannot be used to check compliance of UTZ certified farms with the UTZ standard.)

More sustainable farming methods

Conventional farming methods can damage soils and waterways, reducing crop productivity. When land goes fallow, farmers may be tempted to cut down nearby forests for new, fertile earth—and so begins a destructive cycle: raze, plant, deplete, repeat. (Though to be clear, industrial farming, not smallholder farming, that drives the kind of large-scale deforestation that truly threatens our planet.) More sustainable agriculture techniques lead to healthier soils, cleaner waterways, and better yields.

In Sri Lanka, nearly 100 tea farmers received Rainforest Alliance trainings in natural and manual pest control, which saves money usually spent on agrochemicals and also improves yields. Smallholder tea farmer Saman Udayakumara saw concrete benefits from applying the knowledge he gained in our workshops. “We were the only estate to continue plucking this year during the drought. We can see healthy tea bushes now, a better spread of branches, and more crop as a result.”

Agroforestry

Some crops, like coffee and cocoa, grow beautifully under the shade of larger trees. Nurturing existing trees and planting new ones side-by-side with crops—a practice called agroforestry—can bring a host of environmental benefits: On-farm trees can help connect forest fragments, which benefits migratory species; a protective canopy regulates temperature and humidity, and many types of shade trees improve the health of the soil; fruit-bearing shade-trees, such as bananas and mangos, can provide additional income.

In West Java, Indonesia, a coffee cooperative called Klasik Beans has taken agroforestry to impressive lengths, in part to help prevent the kind of deadly landslide that killed thousands in 2004—a landslide caused by deforestation. Klasik’s Rony Syahroni explains, “We don’t plant coffee in the forest—we design our farms to become forests.”

Reducing bushmeat hunting

Meat from wild animals—including endangered species—has long provided an important source of protein and supplementary income for farmers across West Africa. But surging demand for bushmeat, coupled with deforestation for logging and mining, have vastly increased the scale of hunting—as well as the opportunity for pathogens to jump from wild animals to humans. In Côte d’Ivoire’s Taï National Park, one of the last remaining areas of primary forest, the Rainforest Alliance works with six cocoa communities on the park’s southern edge to farm in ways that defend the forest. In addition to 500 farmers using more sustainable and climate-smart methods, restoring ecosystems, and boosting productivity on existing farmland, more than 80 farmers have begun rearing chickens and keeping bees as an alternative to hunting bushmeat.

Similarly, in Ghana, cocoa farmers we work with in Juaboso-Bia raise grasscutters, considered a delicacy, as an alternative to hunting, and they also practice responsible beekeeping. These projects, tailored to local needs and conditions, reduce the interaction of humans and wildlife and protect the forests we need so badly to help slow climate change.