The lush Appalachian woodlands of the southeastern United States are an ecological treasure. With 158 tree species, the region ranks as one of North America’s highest in total floral diversity; it is also the world’s center for lungless salamander diversity, featuring 34 species of lungless salamanders. All told, the Appalachian woodlands represent one of the world’s richest temperate forests.

More than 15,000 documented species, including endemic land snail, amphibian, and herbaceous plant populations, thrive in the region. The region’s Little Tennessee and Clinch Rivers boast the highest diversity of freshwater shellfish and salamanders on the planet. And like all living forests, the Appalachian woodlands are the lungs of the region, providing clean oxygen while also absorbing greenhouse gases and stabilizing the local climate.

Nearly 60 percent of these forests are owned and managed by private landowners—families, small businesses, or a single person—who regard their forest as a living asset for recreation, refuge, and a source of income. The privately-held forestland in this region spawns billions of dollars worth of forest products each year. This land is considered an important legacy in a historically impoverished region, to be handed down from generation to generation. Forest product companies have worked to establish longstanding, mutually beneficial partnerships with landowners, extracting raw timber to be processed in mills and factories. These companies have created their own local legacy: the employment of generations of workers in the region for more than a century.

“In the past, there was bad forest management in the form of coal and gas exploitation, strip mining, mountaintop removal, and other practices that deteriorated the landscape. But now we’re in recovery and restoration mode.”

Andrew Goldberg, the Rainforest Alliance’s project manager for the Appalachian Woodlands Alliance

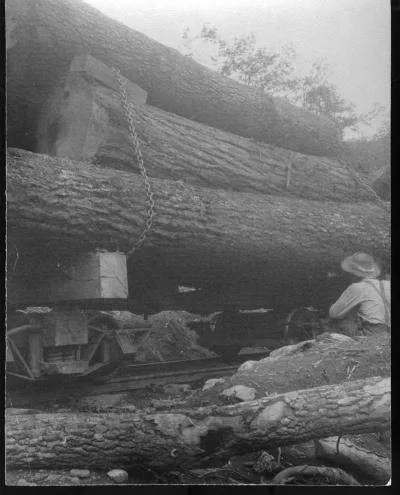

An unsustainable history

In years past, the industry practiced clear-cutting forests and selective tree harvesting—leaving degraded land in the wake of a short-lived economic boost. For landowners, a clear-cut forest meant waiting two or three generations until the trees grew back before undertaking another harvest—taking an important source of income for both landowners and forestry workers in the region off the table during these down cycles. While many private woodland owners across the area have an excellent record of forest stewardship, irresponsible harvesting was the norm, rather than the exception, for decades.The products that come out of these forests are things we all use every day—copy paper, wood for construction, even the price tags on clothing—and the economic impact of the forest products industry in the region cannot be overstated. But it is in everybody’s best interest—the industry’s, the landowners’, the birds’—to keep these forests standing.

The Appalachian Woods Alliance

To address these pressures on a critically important US landscape, the Rainforest Alliance has joined with businesses, foresters, the US Forest Service, and landowners in the southeast United States to form the Appalachian Woods Alliance (AWA). The AWA works to conserve this forestland and enhance the local economy by advancing sustainable forest management practices tailored to local needs. For the southern and central Appalachians, these practices include proven conservation measures, such as the creation of vegetative buffers alongside waterways to enhance water quality, the management of invasive species, and the improvement of high-value habitats such as those that house migratory birds and other critical wildlife.

“This is a hardworking landscape with a long history,” says Andrew Goldberg, the Rainforest Alliance’s project manager for the Appalachian Woodlands Alliance. “In the past, there was bad forest management in the form of coal and gas exploitation, strip mining, mountaintop removal, and other practices that deteriorated the landscape. But now we’re in recovery and restoration mode.” Goldberg works closely with the other members of the AWA to make sustainable forest management the new norm in the region. The members include the US Forestry Service; leading forest product companies Avery Dennison, Columbia Forest Products, Domtar, Evergreen Packaging, Staples, and Kimberly-Clark; and an advisory board of diverse stakeholders (scientists, academics, landowners, as well as corporate and nonprofit representatives). The three-year project, which began in 2015, focuses on an area in the Appalachian forest that is approximately the size of West Virginia. Encompassing parts of Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina, the AWA project area covers tens of thousands of landowners in 15 communities.The project has five main objectives:

- Increasing understanding and appreciation of the inherent benefits of sustainable forest management practices among woodland owners;

- Demonstrating the compatibility and interdependence of sustainable forest management practices with the social and economic wellbeing of local communities, healthy forest ecosystems, and values held by woodland owners;

- Increasing the number of woodland owners actively engaged in sustainable forest management, and therefore increasing availability of sustainably-produced forest products;

- Promoting and maintaining biodiversity and healthy ecosystems, including the monitoring of indicator species like migratory birds; and

- Accurately measuring and effectively communicating project results.

Landowners in the Southeast

The South is well known for having deeply rooted family values, and the Southeastern forests of the United States reflect that tradition. “That landscape is owned by private woodland owners. Their decisions about how they manage the land have tremendous impacts,” says Goldberg. “What we’re doing now is helping to keep the forests as forests—making it so sustainable forest management is the best option for landowners. So we’re increasing demand for sustainably produced wood products, assisting landowners with the technical aspects of sustainable forestry, and coming up with ideas together.”

In a region where nearly 60 percent of the land is privately owned, engaging with landowners is one of the most important aspects of the AWA. With sustainable forest management as the goal, certification according to Forest Stewardship Council® standards is one, but not the only, option. It’s important to define a path to responsible forest management that is flexible for private landowners without compromising conservation values. Landowners use their land for personal recreation, hunting, and fishing, among other uses—and working with them to establish a system of sustainable forest management practices that takes these uses into account is a cornerstone of the AWA.

Forest product companies

The incredible diversity of tree species and quick natural regeneration of Southeastern forests have drawn numerous mills and factories to the area for more than a century. In partnership with the Rainforest Alliance, the companies aligned with the AWA seek to work with landowners and grow the number of those who are FSC certified or utilize sustainable forest management methods that are in line with the core values of the project. Using FSC certification as a standard or model ensures that the raw materials used to make hardwood products are harvested with comprehensive sustainability as a top priority.

The majority of forests in the area are privately owned, so mills in the Southeast region rely heavily upon these small parcels of land; in fact, 70 to 90 percent of the raw materials mills use in this area, come from privately held forestlands. Mills within the project area provide local jobs, purchase millions of dollars of timber annually, and collectively have more than a billion-dollar impact on the region. Promoting sustainable forest management through one of the region’s primary economic engines is a critical part of maintaining and improving the health of these forests. Through the AWA, the Rainforest Alliance is working to enhance the health of these forests and bolster sustainable livelihoods that support long-term forest conservation.