Through our education program, led by Maria Ghiso, we are working with young people from the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, in Campeche, Mexico, to look at the rainforest with an eye toward their futures.

After falling asleep to the sound of rain tapping the metal roof of our cabin, we woke to a clear, sunny day. Rain would not have put a damper on the enthusiasm of our group, however, which included 11 young people (age 16 – 22), my colleague Ann Snook, our local consultants, and me. The youth had come from various communities in the state of Campeche, Mexico, to visit an ancient mahogany forest in the nearby Noh Bec ejido (communally owned and operated land), where this part of the forest had been set aside for seed trees, conservation, and tourism.

It may be surprising that these young people would be playing tourist here, since they themselves all hail from ejidos in the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, a stretch of dense, lush tropical forest that is a UNESCO World Heritage site. But this is precisely why the Rainforest Alliance chose them: a baseline assessment showed that the youth in ejidos are very interested in someday working in their communities but see few prospects, while the older generation currently in charge assume the young people have no interest. As part of our landscape conservation work in the region, we launched an initiative to teach young people about their environment and the forest enterprises in their ejidos so that they could envision a future in their home communities. Our aim here is to help prevent out-migration so that these important conservation areas don’t lose the energetic, innovative young people who will be critical to maintaining and strengthening sustainable forest enterprises in the future.

Ejidos, a land tenure system in which land is cooperatively managed by a community, are partly why Mexico’s forestry sector is one of the most advanced on Earth. While this system dates back to the Mexican Revolution, local communities have only come to exercise full control over their forests in the last few decades, and they have since built successful, sustainable forest enterprises that include timber extraction and allspice and honey extraction. From a conservation standpoint, ejidos have been a success, but their traditional structure effectively sidelines many young people: only male heads of households of founding families can vote on community matters, own land, or otherwise participate in the decision-making of the ejido. Young people—even the son of a founding member—can’t participate in assembly meetings at all, so familiarity with the cooperative’s workings is scant among youth. (In very rare cases, ejidos have set aside lands for interested young people.) As a result of this perceived lack of opportunity, youth are likely to move away as young adults to seek work elsewhere.

To retain some of this youthful talent and energy in the ejido, we began working with local young people, most of whom attend a technical forestry school in Zoh Laguna, Campeche, in early 2016. Since then we have provided more than 200 hours of workshops to a core group of about 20 students, introducing them to experts in the field and helping them learn about different opportunities—from traditional forestry jobs to possible new niches they could fill in the future, even if they don’t stand to inherit voting rights or land. We engage the students by emphasizing the skills and interests that young people tend to have already: technology, climate-based science, and marketing know-how. We’ve also taken the students on many field trips, walking through the forest, measuring trees, and conducting scientific studies and observations. The forest in this region of Mexico is part of the largest contiguous forest north of the Amazon, with iconic species and hundreds of fascinating Maya ruins that tell the story of a highly sophisticated ancient civilization.

Getting to know these ecologically precious forests has been poignant for many of our young participants. On one excursion, we saw a king vulture—an impressively huge bird that can grow to be 32 inches. Afterward, one young woman, Carmelina Martínez Hernández, sheepishly said that while she had been delighted to see the famously skittish creature in person, she’d been most moved by the mere act of walking deep in the forest—a first for her and many of these town-dwelling young people.

Appreciation for the forest has led to a passion for conserving it: one of our more musical members, Espiridión Gómez Jimenez has even composed a rap song on the subject with a friend.

On today’s visit to the ancient forest of Noh Bec, the students are laughing and singing as we walk along, much like you’d expect from any group of young people, when we come upon a giant, ancient tree. The chatting stops abruptly, and our participants gaze upward in silence, their faces full of awe. One of them asks aloud how big the tree might be, and soon they are linking hands to see how many people it takes to form a human chain around this hundred-year-old mahogany.

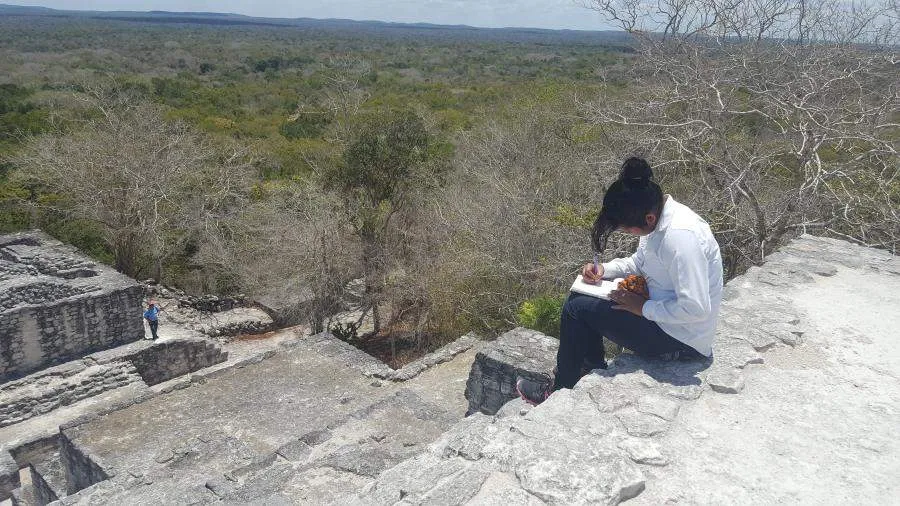

I’m moved by their curiosity and excitement to learn; at every meeting with a forestry expert or visit to a business, the participants whip out their notebooks and furiously scribble notes or take pictures with their phones. Once shy about interviewing even family members, now the students—after more than a year of working with us—ask all the technicians and experts they meet where they studied, how they got their jobs, and what they think of their work. In the evening, after a long day in the forest, we sit around the campfire and the students share their hopes and dreams for their future. Most of them now aim to develop careers in sustainability and conservation, and many of them will work to do that in their own ejidos.

Until that time, we continue to work with these delightful young people, who often text me out of the blue to ask, “What’s our next adventure going to be?” We are currently working with the ejidos and a local forestry consulting firm to create opportunities, such as internships or apprenticeships, so that the participants can get some practical experience—and ejido managers can see the youths’ potential. One thing I know from experience: it doesn’t take much time with these young people to feel hope for the future of the forest.